We want OpenStack to work as a universal cloud API but it’s hard! What’s the problem?

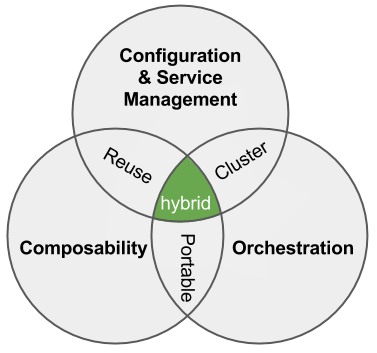

This post, written before the Tokyo Summit but not published, talks about how we got here without a common standard and offers some pointers. At the Austin Summit, I’ve got a talk on hybrid Open Infrastructure Wednesday @ 2:40 where I talk specifically about solutions. I’ve been working on multi-infrastructure hybrid – that means making ops portable between OpenStack, Google, Amazon, Physical and other options.

This post, written before the Tokyo Summit but not published, talks about how we got here without a common standard and offers some pointers. At the Austin Summit, I’ve got a talk on hybrid Open Infrastructure Wednesday @ 2:40 where I talk specifically about solutions. I’ve been working on multi-infrastructure hybrid – that means making ops portable between OpenStack, Google, Amazon, Physical and other options.

The Problem: At a fundamental level, OpenStack has yet to decide if it’s an infrastructure (IaaS) product or a open software movement.

Is there a path to be both? There are many vendors who are eager to sell you their distinct flavor of OpenStack; however, lack of consistency has frustrated users and operators. OpenStack faces internal and external competition if we do not address this fragmentation. Over the next few paragraphs, we’ll explore the path the Foundation has planned to offer users a consistent core product while fostering its innovative community.

How did we get down this path? Here’s some background how how we got here.

Before we can discuss interoperability (interop), we need to define success for OpenStack because interop is the means, not the end. My mark for success is when OpenStack has created a sustainable market for products that rely on the platform. In business plan speak, we’d call that a serviceable available market (SAM). In practical terms, OpenStack is successful when businesses targets the platform as the first priority when building integrations over cloud behemoths: Amazon and VMware.

The apparent dominance of OpenStack in terms of corporate contribution and brand position does not translate into automatic long term success.

While apparently united under a single brand, intentional technical diversity in OpenStack has lead to incompatibilities between different public and private implementations. While some of these issues are accidents of miscommunication, others were created by structural choices inherent to the project’s formation. No matter the causes, they frustrate users and limit the network effect of widespread adoption.

Technical diversity was both a business imperative and design objective for OpenStack during formation.

In order to quickly achieve critical mass, the project needed to welcome a diverse and competitive set of corporate sponsors. The commitment to support operating systems, multiple hypervisors, storage platforms and networking providers has been essential to the project’s growth and popularity. Unfortunately, it also creates combinatorial complexity and political headaches.

With all those variables, it’s best to think of interop as a spectrum.

At the top of that spectrum is basic API compatibility and the boom is fully integrated operation where an application could run site unaware in multiple clouds simultaneously. Experience shows that basic API compatibility is not sufficient: there are significant behavioral impacts due to implementation details just below the API layer that must also be part of any interop requirement. Variations like how IPs are assigned and machines are initialized matter to both users and tools. Any effort to ensure consistency must go beyond simple API checks to validate that these behaviors are consistent.

OpenStack enforces interop using a process known as DefCore which vendors are required to follow in order to use the trademark “OpenStack” in their product name.

The process is test driven – vendors are required to pass a suite of capability tests defined in DefCore Guidelines to get Foundation approval. Guidelines are published on a 6 month cadence and cover only a “core” part of OpenStack that DefCore has defined as the required minimum set. Vendors are encouraged to add and extend beyond that base which then leads for DefCore to expand the core based on seeing widespread adoption.

What is DefCore? Here’s some background about that too!

By design, DefCore started with a very small set of OpenStack functionality. So small in fact, that there were critical missing pieces like networking APIs from the initial guideline. The goal for DefCore is to work through the coabout mmunity process to expand based identified best practices and needed capabilities. Since OpenStack encourages variation, there will be times when we have to either accept or limit variation. Like any shared requirements guideline, DefCore becomes a multi-vendor contract between the project and its users.

Can this work? The reality is that Foundation enforcement of the Brand using DefCore is really a very weak lever. The real power of DefCore comes when customers use it to select vendors.

Your responsibility in this process is to demand compliance from your vendors. OpenStack interoperability efforts will fail if we rely on the Foundation to enforce compliance because it’s simply too late at that point. Think of the healthy multi-vendor WiFi environment: vendors often introduce products on preliminary specifications to get ahead of market. For success, OpenStack vendors also need to be racing to comply with the upcoming guidelines. Only customers can create that type of pressure.

From that perspective, OpenStack will only be as interoperable as the market demands.

That creates a difficult conundrum: without common standards, there’s no market and OpenStack will simply become vertical vendor islands with limited reach. Success requires putting shared interests ahead of product.

That brings us full circle: does OpenStack need to be both a product and a community? Yes, it clearly does.

The significant distinction for interop is that we are talking about a focus on the user community voice over the vendor and developer community. For that, OpenStack needs to focus on product definition to grow users.

I want to thank Egle Sigler and Shamail Tahir for their early review of this post. Even beyond the specific content, they have helped shape my views on this topics. Now, I’d like to hear your thoughts about this! We need to work together to address Interoperability – it’s a community thing.

Here’s the summary:

Here’s the summary: This post, written before the Tokyo Summit but not published, talks about how we got here without a common standard and offers some pointers. At the Austin Summit, I’ve got a talk on hybrid

This post, written before the Tokyo Summit but not published, talks about how we got here without a common standard and offers some pointers. At the Austin Summit, I’ve got a talk on hybrid

Here’s our write-up:

Here’s our write-up:

awareness, you can be more secure WITHOUT putting more work for developers.

awareness, you can be more secure WITHOUT putting more work for developers. 2016 is the year we break down the monoliths. We’ve spent a lot of time talking about monolithic applications and microservices; however, there’s an equally deep challenge in ops automation.

2016 is the year we break down the monoliths. We’ve spent a lot of time talking about monolithic applications and microservices; however, there’s an equally deep challenge in ops automation.