Today at Dell, I was presenting to our storage teams about cloud storage (aka the “storage banana”) and Dave “Data Gravity” McCrory reminded me that I had not yet posted my epiphany explaining “why cloud compute will be free.” This realization derives from other topics that he and I have blogged but not stated so simply.

Today at Dell, I was presenting to our storage teams about cloud storage (aka the “storage banana”) and Dave “Data Gravity” McCrory reminded me that I had not yet posted my epiphany explaining “why cloud compute will be free.” This realization derives from other topics that he and I have blogged but not stated so simply.

Overlooking that fact that compute is already free at Google and Amazon, you must understand that it’s a cloud eat cloud world out there where losing a customer places your cloud in jeopardy. Speaking of Jeopardy…

Answer: Something sought by cloud hosts to make profits (and further the agenda of our AI overlords).

Question: What is lock-in?

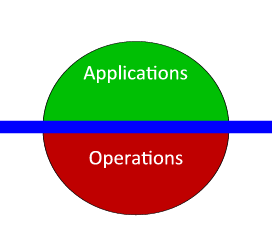

Hopefully, it’s already obvious to you that clouds are all about data. Cloud data takes three primary forms:

- Data in transformation (compute)

- Data in motion (network)

- Data at rest (storage)

These three forms combine to create cloud architecture applications (service oriented, externalized state).

The challenge is to find a compelling charge model that both:

- Makes it hard to leave your cloud AND

- Encourages customers to use your resources effectively (see #1 in Azure Top 20 post)

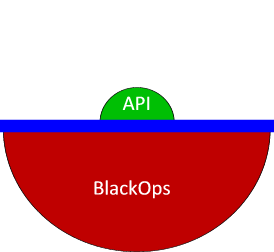

While compute demands are relatively elastic, storage demand is very consistent, predictable and constantly grows. Data is easily measured and difficult to move. In this way, data represents the perfect anchor for cloud customers (model rule #1). A host with a growing data consumption foot print will have a long-term predictable revenue base.

However, storage consumption along does not encourage model rule #2. Since storage is the foundation for the cloud, hosts can fairly judge resource use by measuring data egress, ingress and sidegress (attrib @mccrory 2/20/11). This means tracking not only data in and out of the cloud, but also data transacted between the providers own cloud services. For example, Azure changes for both data at rest ($0.15/GB/mo) and data in motion ($0.01/10K).

Consequently, the financially healthiest providers are the ones with most customer data.

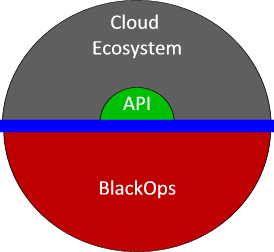

If hosting success is all about building a larger, persistent storage footprint then service providers will give away services that drive data at rest and/or in motion. Giving away compute means eliminating the barrier for customers to set up web sites, develop applications, and build their business. As these accounts grow, they will deposit data in the cloud’s data bank and ultimately deposit dollars in their piggy bank.

However, there is a no-free-lunch caveat: free compute will not have a meaningful service level agreement (SLA). The host will continue to charge for customers who need their applications to operate consistently. I expect that we’ll see free compute (or “spare compute” from the cloud providers perspective) highly used for early life-cycle (development, test, proof-of-concept) and background analytic applications.

The market is starting to wake up to the idea that cloud is not about IaaS – it’s about who has the data and the networks.

Oh, dem golden spindles! Oh, dem golden spindles!