In my opinion, one of the biggest challenges facing companies like Dell, my employer, is how to help package and deliver this thing called cloud into the market. I recently had the opportunity to watch and listen to customers try to digest the concept of PaaS.

PaaS.

While not surprising, the technology professionals in the room split into across four major cultural camps: enterprise vs. start-up and dev vs. ops. Because I have a passing infatuation with pastel cloud shaped quadrant graphs, I was able to analyze the camps for some interesting insights.

The camps are:

- Imperialists: These enterprise type developers are responsible for adapting their existing business to meet the market. They prefer process oriented tools like Microsoft .Net and Java that have proven scale and supportability.

- MacGyvers: These startup type developers are under the gun to create marketable solutions before their cash runs out. They prefer tools that adapt quick, minimize development time and community extensions.

- Crown Jewels: These enterprise type IT workers have to keep the email and critical systems humming. When they screw up everyone notices. They prefer systems where they can maintain control, visibility, or (better) both.

- Legos: These start-up type operations jugglers are required to be nimble and responsive with shoestring budgets. They prefer systems that they can change and adapt quickly. They welcome automation as long as they can maintain control, visibility, or (better) both.

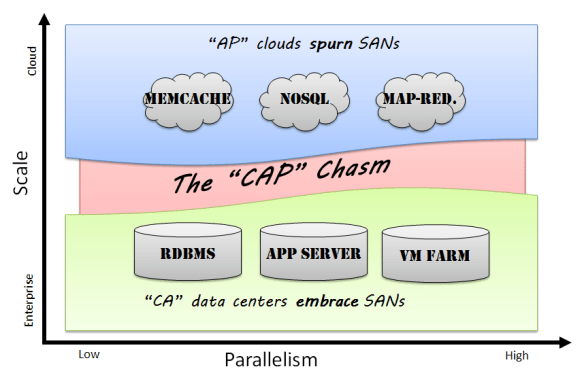

This graph is deceiving because it underplays the psychological break caused by willingness to take risks. This break creates a cloud culture chasm.

On one side, the reliable Imperialists want will mount a Royal Navy flotilla to protect the Crown Jewels in a massive show of strength. They are concerned about the security and reliability of cloud technologies.

On the other side, the MacGyvers are working against a ticking time bomb to build a stealth helicopter from Legos they recovered from Happy Meals™. They are concerned about getting out of their current jam to compile another day.

Normally Imperialists simply ignore the MacGyvers or run down the slow ones like yesterday’s flotsam. The cloud is changing that dynamic because it’s proving to be a dramatic force multiplier in several ways:

- Lower cost of entry – the latest cloud options (e.g. GAE) do not charge anything unless you generate traffic. The only barrier to entry is an idea and time.

- Rapid scale – companies can fund growth incrementally based on success while also being able to grow dramatically with minimal advanced planning.

- Faster pace of innovation – new platforms, architectures and community development has accelerated development. Shared infrastructure means less work on back office and more time on revenue focused innovation.

- Easier access to customers – social media and piggy backing on huge SaaS companies like Facebook, Google or SalesForce bring customers to new companies’ front doors. This means less work on marketing and sales and more time on revenue focused innovation.

The bottom line is that the cloud is allowing the MacGyvers to be faster, stronger, and more innovative than ever before. And we can expect them to be spending even less time polishing the brass in the back office because current SaaS companies are working hard to help make them faster and more innovative.

For example, Facebook is highly incented for 3rd party applications to be innovative and popular not only because they get a part of the take, but because it increases the market strength of their own SaaS application.

So the opportunity for Imperialists is to find a way for employee and empower the MacGyvers. This is not just a matter of buying a box of Legos: the strategy requires tolerating enabling embracing a culture of revenue focused innovation that eliminates process drag. My vision does not suggest a full replacement because the Imperialists are process specialists. The goal is to incubate and encapsulate cloud technologies and cultures.

So our challenge is more than picking up cloud technologies, it’s understanding the cloud communities and cultures that we are enabling.