Why did your mom care about underwear? She wanted you to have good hygiene. What is good Ops hygiene? It’s not as simple as keeping up with the laundry, but the idea is similar. It means that we’re not going to get surprised by something in our environment that we’d taken for granted. It means that we have a fundamental level of control to keep clean. Let’s explore this in context.

I’ve struggled with the term “underlay” for infrastructure of a long time. At RackN, we generally prefer the term “ready state” to describe getting systems prepared for install; however, underlay fits very well when we consider it as the foundation for a more building up a platform like Kubernetes, Docker Swarm, Ceph and OpenStack. Even more than single operator applications, these community built platforms require carefully tuned and configured environments. In my experience, getting the underlay right dramatically reduces installation challenges of the platform.

I’ve struggled with the term “underlay” for infrastructure of a long time. At RackN, we generally prefer the term “ready state” to describe getting systems prepared for install; however, underlay fits very well when we consider it as the foundation for a more building up a platform like Kubernetes, Docker Swarm, Ceph and OpenStack. Even more than single operator applications, these community built platforms require carefully tuned and configured environments. In my experience, getting the underlay right dramatically reduces installation challenges of the platform.

What goes into a clean underlay? All your infrastructure and most of your configuration.

Just buying servers (or cloud instances) does not make a platform. Cloud underlay is nearly as complex, but let’s assume metal here. To turn nodes into a cluster, you need setup their RAID and BIOS. Generally, you’ll also need to configure out-of-band management IPs and security. Those RAID and BIOS settings specific to the function of each node, so you’d better get that right. Then install the operating system. That will need access keys, IP addresses, names, NTP, DNS and proxy configuration just as a start. Before you connect to the wide, make sure to update to your a local mirror and site specific requirements. Installing Docker or a SDN layer? You may have to patch your kernel. It’s already overwhelming and we have not even gotten to the platform specific details!

Buried in this long sequence of configurations are critical details about your network, storage and environment.

Any mistake here and your install goes off the rails. Imagine that your building a house: it’s very expensive to change the plumbing lines once the foundation is poured. Thankfully, software configuration is not concrete but the costs of dealing with bad setup is just as frustrating.

The underlay is the foundation of your install. It needs to be automated and robust.

The challenge compounds once an installation is already in progress because adding the application changes the underlay. When (not if) you make a deploy mistake, you’ll have to either reset the environment or make your deployment idempotent (meaning, able to run the same script multiple times safely). Really, you need to do both.

Why do you need both fast resets and component idempotency? They each help you troubleshoot issues but in different ways. Fast resets ensure that you understand the environment your application requires. Post install tweaks can mask systemic problems that will only be exposed under load. Idempotent action allows you to quickly iterate over individual steps to optimize and isolate components. Together they create resilient automation and good hygiene.

In my experience, the best deployments involved a non-recoverable/destructive performance test followed by a completely fresh install to reset the environment. The Ops equivalent of a full dress rehearsal to flush out issues. I’ve seen similar concepts promoted around the Netflix Chaos Monkey pattern.

If your deployment is too fragile to risk breaking in development and test then you’re signing up for an on-going life of fire fighting. In that case, you’ll definitely need all the “clean underware” you can find.

We think Kubernetes is an awesome way to run applications at scale! Unfortunately, there’s a bootstrapping problem: we need good ways to build secure & reliable scale environments around Kubernetes. While some parts of the platform administration leverage the platform (cool!), there are fundamental operational topics that need to be addressed and questions (like upgrade and conformance) that need to be answered.

We think Kubernetes is an awesome way to run applications at scale! Unfortunately, there’s a bootstrapping problem: we need good ways to build secure & reliable scale environments around Kubernetes. While some parts of the platform administration leverage the platform (cool!), there are fundamental operational topics that need to be addressed and questions (like upgrade and conformance) that need to be answered. Here’s the summary:

Here’s the summary: Here’s our write-up:

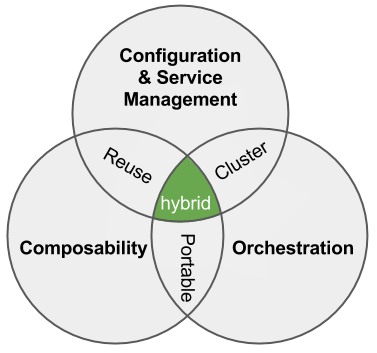

Here’s our write-up:  2016 is the year we break down the monoliths. We’ve spent a lot of time talking about monolithic applications and microservices; however, there’s an equally deep challenge in ops automation.

2016 is the year we break down the monoliths. We’ve spent a lot of time talking about monolithic applications and microservices; however, there’s an equally deep challenge in ops automation. I’ve struggled with the term “underlay” for infrastructure of a long time. At

I’ve struggled with the term “underlay” for infrastructure of a long time. At