As I’m working on a larger “cloud bootstrapping” white paper (look for a pending Dell release), I stumbled on an apparent unifying principle for hyperscale cloud design. I’m interested in feedback about this concept to see if it fairly encapsulates a common target for cloud hardware, networking and software design.

As I’m working on a larger “cloud bootstrapping” white paper (look for a pending Dell release), I stumbled on an apparent unifying principle for hyperscale cloud design. I’m interested in feedback about this concept to see if it fairly encapsulates a common target for cloud hardware, networking and software design.

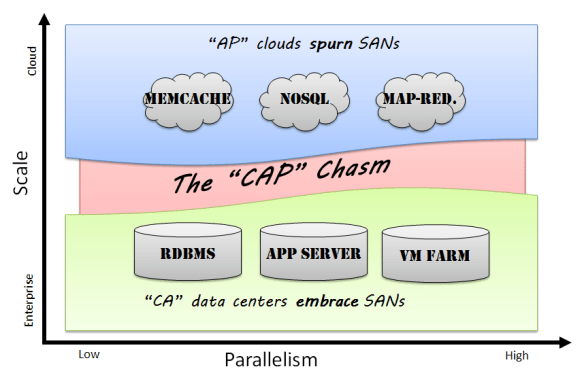

“Flatness at the Edges” is one of the guiding principles of hyperscale cloud designs.

Flatness means that cloud infrastructure avoids creating tiers where possible. For example, having a blade in a frame aggregating networking that is connected to a SAN via a VLAN is a tiered design in which the components are vertically coupled. A single node with local disk connected directly to the switch has all the same components but in a single “flat” layer.

Edges are the bottom tier (or “leaves” to us CS geeks) of the cloud. Being flat creates a lot of edges because most of the components are self contained. To scale and reduce complexity, clouds must rely on the edges to make independent decisions such as how to route network traffic, where to replicate data, or when to throttle VMs. The anti-example of edge design is using VLANs to segment tenants because VLANs (a limited resource) require configuration at the switching tier to manage traffic generated by an edge component. We are effectively distributing an intelligence overhead tax on each component of the cloud rather than relying on a “centralized overcloud” to rule them all.

Combining flatness and edges evolves the sympathetic concepts into full-fledged cloud design principle.

Interested in discussing this face to face? I’ll presenting this and other cloud setup concepts that the SJC OpenStack meetup on 2/3.

I’m growing more and more concerned about the preponderance of Frankencloud offerings that I see being foisted into the market place (no, my employer,

I’m growing more and more concerned about the preponderance of Frankencloud offerings that I see being foisted into the market place (no, my employer,