Tonight I submitted a formal OpenStack Common blue print for Crowbar as a cloud installer. My team at Dell considers this to be our first step towards delivering the code as open source (next few weeks) and want to show the community the design thinking behind the project. Crowbar currently only embodies a fraction of this scope but we have designed it looking forward.

Tonight I submitted a formal OpenStack Common blue print for Crowbar as a cloud installer. My team at Dell considers this to be our first step towards delivering the code as open source (next few weeks) and want to show the community the design thinking behind the project. Crowbar currently only embodies a fraction of this scope but we have designed it looking forward.

I’ve copied the text of our inital blueprint here until it is approved. The living document will be maintained at the OpenStack launch pad and I will update links appropriately.

Here’s what I submitted:

Note: Installer is used here because of convention. The scope of this blue print is intended to include expansion and maintenance of the OpenStack infrastructure.

Summary

This blueprint creates a common installation system for OpenStack infrastructure and components. The installer should be able to discover and configure physical equipment (servers,switches, etc) and then deploy the OpenStack software components in an optimum way for the discovered infrastructure. Minimum manual steps should be needed for setup and maintenance of the system.

Users should be able to leverage and contribute to components of the system without deploying 100% of the system. This encourages community collaboration. For example, installation scripts that deploy and configure OpenStack components should be usable without using bare metal configuration and vice-versa.

The expected result will be installations that are 100% automated after racking gear with no individual touch of any components.

This means that the installer will be able to

- expand physical capacity

- update of software components

- addition of new software components

- cope with heterogeneous environments (hardware, OpenStack components, hyper-visors, operating systems, etc)

- handle rolling upgrades (due to the scale of OpenStack target deployments)

Release Note

Not currently released. Reference code (“Crowbar”) to be delivered by Dell via GitHub .

Rationale / Problem Statement

While a complete deployment system is an essential component to ensure adoption, it also fosters sharing and encoding of operational methods by the community. This follows and “Open Ops” strategy that encourages OpenStack users to create and share best practices.

The installer addresses the following needs

- Community collaboration on deployment scripts and architecture.

- Bare metal installation – this is different, but possibly related to Nova bare metal provisioning

- OpenStack is evolving (Ops Model, CloudOps )

- Provide a common installation platform to facilitate consistent deployments

It is important that the installer does NOT

- constrain architecture to limit scale

- create extra effort to re-balance as system capacity grows

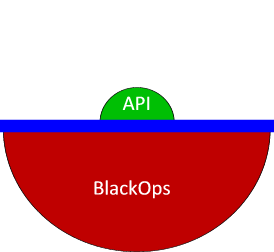

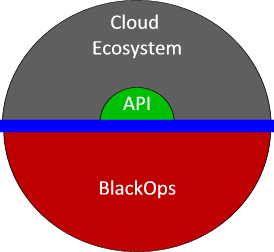

This design includes an “Ops Infrastructure API” for use by other components and services. This REST API will allow trusted applications to discover and inspect the operational infrastructure to provide additional services. The API should expose

- Managed selection of components & requests

- Expose internal infrastructure (not for customer use, but to enable Ops tools)

- networks

- nodes

- capacity

- configuration

Assumptions

- OpenStack code base will not limit development based on current architecture practices. Cloud architectures will need to adopt

- Expectation to use IP-based system management tools to provide out of band reboot and power controls.

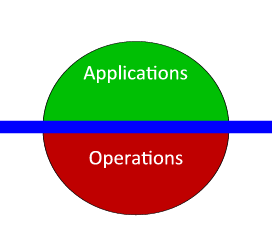

Design

The installation process has multiple operations phases: 1) bare metal provisioning, 2) component deployment, and 3) upgrade/redeployment. While each phase is distinct, they must act in a coordinated way.

A provisioning state machine (PSM) is a core concept for this overall installation architecture. The PSM must be extensible so that new capabilities and sequences can be added.

It is important that installer support IPv6 as an end state. It is not required that the entire process be IPv4 or IPv6 since changing address schema may be desirable depending on the task to be performed.

Modular Design Objective

- should have a narrow focus for installation – a single product or capability.

- may have pre-requisites or dependencies but as limited as possible

- should have system, zone, and node specific configuration capabilities

- should not interfere with operation of other modules

Phase 1: Bare Metal Provisioning

- For each node:

- Entry State: unconfigured hardware with network connectivity and PXE boot enabled.

- Exit State: minimal node config (correct operating system installed, system named and registered, checked into OpenStack install manager)

The core element for Phase 1 is a “PXE State Machine” (a subset of the PSM) that orchestrates node provisioning through multiple installation points. This allows different installation environments to be used while the system is prepared for it’s final state. These environments may include BIOS & RAID configuration, diagnostics, burn-in, and security validation.

It is anticipated that nodes will pass through phase 1 provisioning FOR EACH boot cycle. This allows the Installation Manager to perform any steps that may be dictated based on the PSM. This could include diagnostic and security checks of the physical infrastructure.

Considerations:

- REST API for updating to new states from nodes

- PSM changes PXE image based on state updates

- PSM can use IPMI to force power changes

- DHCP reservations assigned by MAC after discovery so nodes have a predictable IP

- Phase 1 images may change IP addresses during this phase.

- Discovery phase would use short term DHCP addresses. The size of the DHCP lease pool may be restricted but should allow for provisioning a rack of nodes at a time.

- Configuration parameters for Phase 1 images can be passed

- via DHCP properties (preferred)

- REST data

- Discovery phase is expected to set the FQDN for the node and register it with DNS

Phase 2: Component Deployment

- Entry State: set of nodes in minimal configuration (number required depends on components to deploy, generally >=5)

- Requirements:

- Exit State: one or more

During Phase 2, the installer must act on the system as a whole. The focus shifts from single node provisioning, to system level deployment and configuration.

Phase 2 extends the PSM to comprehend the dependencies between system components. The use of a state machine is essential because system configuration may require that individual nodes return to Phase 1 in order to change their physical configuration. For example, a node identified for use by Swift may need to be setup as a JBOD while the same node could be configured as RAID 10 for Nova. The PSM would also be used to handle inter-dependencies between components that are difficult to script in stages such as rebalancing a Swift ring.

Considerations:

- Deployments must be infrastructure aware so they can take network topology, disk capacity, fault zones, and proximity into account.

- System must generate a reviewable proposal for roles nodes will perform.

- Roles (nodes may have >1 role) define OS & prerequisite components that execute on on nodes

- Operations on nodes should be omnipotent for individual actions (multiple state operations will violate this principle by definition)

- System wide configuration information must be available to individual configuration nodes (e.g.: Scheduler must be able to retrieve a list of all nodes and that list must be automatically updated when new nodes are added).

- Administrators must be able to centrally override global configuration on a individual, rack and zone basis.

- Scripts must be able to identify other nodes and find which roles they were executing

- Must be able to handle non-OS components such as networking, VLANs, load balancers, and firewalls.

Phase 3: Upgrade / Redeployment

The ultimate objective for Phase 3 is to foster a continuous deployment capability in which updates from OpenStack can be frequently and easily implemented in a production environment with minimal risk. This requires a substantial amount of self-testing and automation.

Phase 3 maintains the system when new components arrive. Phase 3 includes the added requirements:

- rolling upgrades so that system operation is not compromised during a deployment

- upgrade/patch of modules

- new modules must be aware of current deployments

- configuration and data must be preserved

- deployments may extend the PSM to to pre-stage operations (move data and vms) before taking action.

Ops API

This needs additional requirements.

The objective of the Ops API is to provide a standard way for operations tools to map the internal cloud infrastructure without duplicating discovery effort. This will allow tools that can:

- create billing data

- audit security

- rebalance physical capacity

- manage power

- audit & enforce physical partitions between tenants

- generate ROI analysis

- IP Address Management (possibly integration/bootstrap with the OpenStack network services)

- Capacity Planning

User Stories

Personas:

- Oscar: Operations Chief

- Knows of Chef or Puppet. Likely has some experience

- Comfortable and likes Linux. Probably prefers CentOS

- Can work with network configuration, but does not own network

- Has used VMware

- Charlie: CIO

- Concerned about time to market and ROI

- Is working on commercial offering based on OpenStack

- Denise: Cloud Developer

- Working on adding features to OpenStack

- Working on services to pair w/ OpenStack

- Comfortable with Ruby code

- Quick: Data Center Worker

- Can operate systems

- In charge of rack and replacement of gear

- Can supervise, but not create automation

Proof of Concept (PoC ) use cases

Agrees to POC

- Charlie agrees to be in POC by signing agreements

- Dell gathers information about shipping and PO delivery

- Quick provides shipping information to Dell

- Oscar downloads ISO and VMPlayer image from Dell provided site.

Get Equipment Setup to base

Event: The Dell equipment has just arrived.

- Quick checks the manifest to make sure that the equipment arrived.

- Quick racks the servers and switch following the wiring chart provided by Oscar

- Quick follows the installation guides BIOS and Raid configuration parameters for the Admin Node

- Quick powers up the servers to make sure all the lights blink then turns them back off

- Oscar arrives with his laptop and the crowbar ISO

- As per instructions, Oscar wires his laptop to the admin server and uses VMplayer to bootstrap the ISO image

- Oscar logs into the VMPlayer image and configures base admin parameters

- Hostname

- networks (admin and public required)

- admin ips

- routers

- masks

- subnets

- usable ranges (mostly for public).

- Optional: ntp server(s)

- Optional: forwarding nameserver(s)

- passwords and accounts

- Manually edits files that get downloaded.

- System validates configuration for syntax and obvious semantic issues.

- System clears switch config and sets port fast and lldp med configuration.

- Oscar powers system and selects network boot (system may automatically do this out of the “box”, but can reset if need be).

- Once the bootstrap and installation of the Ubuntu-based image is completed, Oscar disconnects his laptop from the Admin server and connects into the switch.

- Oscar configures his laptop for DHCP to join the admin network.

- Oscar looks at the Chef UI and verifies that it is running and he can see the Admin node in the list.

- The Install guide will describe this first step and initial passwords.

- The install guide will have a page describing a valid visualization of the environment.

- Oscar powers on the next node in the system and monitors its progress in Chef.

- The install guide will have a page describing this process.

- The Chef status page will have the node arrive and can be monitored from there. Completion occurs when the node is “checked in”. Intermediate states can be viewed by checking the nodes state attribute.

- Node transitions through defined flow process for discovery, bios update, bios setting, and installation of base image.

- Once Oscar sees the node report into Chef, Oscar shows Quick how to check the system status and tells him to turn on the rest of the nodes and monitor them.

- Quick monitors the nodes while they install. He calls Oscar when they are all in the “ready” state. Then he calls Oscar back.

- Oscar checks their health in Nagios and Ganglia.

- If there are any red warnings, Oscar works to fix them.

Install OpenStack Swift

Event: System checked out healthy from base configuration

- Oscar logs into the Crowbar portal

- Oscar selects swift role from role list

- Oscar is presented with a current view of the swift deployment.

- Oscar asks for a proposal of swift layout

- The UI returns a list of storage, auth, proxy, and options.

- Oscar may take the following actions:

- He may tweak attributes to better set deployment

- Use admin node in swift

- Networking options …

- He may force a node out or into a sub-role

- He may re-generate proposal

- He may commit proposal

- Oscar finishes configuration proposal and commits proposal.

- Oscar may validate progress by watching:

- Crowbar main screen to see that configuration has been updated.

- Nagios to validate that services have started

- Chef UI to see raw data..

- Oscar checks the swift status page to validate that the swift validation tests have completed successfully.

- If Swift validation tests fail, Oscar uses troubleshooting guide to correct problems or calls support.

- Oscar uses re-run validation test button to see if corrective action worked.

- Oscar is directed to Swift On-line documentation for using a swift cloud from the install guide.

Install OpenStack Nova

Event: System checked out healthy from base configuration

- Oscar logs into the Crowbar portal

- Oscar selects nova role from role list

- Oscar is presented with a current view of the nova deployment.

- Oscar asks for a proposal of nova layout

- The UI returns a list of options, and current sub-role usage (6 or 7 roles).

- If Oscar has already configured swift, the system will automatically configure glance to use swift.

- Oscar may take the following actions:

- He may tweak attributes to better set deployment

- Use admin node in nova

- Networking options …

- He may force a node out or into a sub-role

- He may re-generate proposal

- He may commit proposal

- Oscar finishes configuration proposal and commits proposal.

- Oscar may validate progress by watching:

- Crowbar main screen to see that configuration has been updated.

- Nagios to validate that services have started

- Chef UI to see raw data..

- Oscar checks the nova status page to validate that the nova validation tests have completed successfully.

- If nova validation tests fail, Oscar uses troubleshooting guide to correct problems or calls support.

- Oscar uses re-run validation test button to see if corrective action worked.

- Oscar is directed to Nova On-line documentation for using a nova cloud from the install guide.

Pilot and Beyond Use Cases

Unattended refresh of system

This is a special case, for Denise.

- Denise is making daily changes to OpenStack’s code base and needed to test it. She has committed changes to their git code repository and started the automated build process

- The system automatically receives that latest code and copies it to the admin server

- A job on admin server sees there is new code resets all the work nodes to “uninstalled” and reboots them.

- Crowbar reimages and reinstalls the images based on its cookbooks

- Crowbar executes the test suites against OpenStack when the install completes

- Denise reviews the test suite report in the morning.

Integrate into existing management

Event: System has passed lab inspection, is about to be connected into the corporate network (or hosting data center)

- Charlie calls Oscar to find out when PoC will start moving into production

- Oscar realizes that he must change from Nagios to BMC on all the nodes or they will be black listed on the network.

- Oscar realizes that he needs to update the SSH certificates on the nodes so they can be access via remote. He also has to change the accounts that have root access.

- Option 1: Reinstall.

- Oscar updates the Chef recipes to remove Nagios and add BMC, copy the cert and configure the accounts.

- Oscar sets all the nodes to “uninstalled” and reimages the system.

- Repeat above step until system is configured correctly

- Option 2: Update Recipes

- Oscar updates the Chef recipes to remove Nagios and add BMC, copy the cert and configure the accounts.

- Oscar runs the Chef scripts and inspects one of the nodes to see if the changes were made

Implementation

We are offering Crowbar as a starting point. It is an extension of Opscode Chef Server that provides the state machine for phases 1 and 2. Both code bases are Apache 2

Test/Demo Plan

TBD

Mascot history

Mascot history