<service bulletin> Server virtualization is not cloud: it is a commonly used technology that creates convenient resource partitions for cloud operations and infrastructure as a service providers. </service bulletin>

OpenStack claims support for nearly every virtualization platform on the market. While the basics of “what is virtualization” are common across all platforms, there are important variances in how these platforms are deployed. It is important to understand these variances to make informed choices about virtualization platforms.

Your virtualization model choice will have deep implications on your server/networking choice, deployment methodology and operations infrastructure.

My focus is on architecture not specific hypervisors so I’m generalizing to just three to make the each architecture description more concrete:

- KVM (open source) is highly used by developers and single host systems

- XenServer (open/freemium) leads public cloud infrastructure (Amazon EC2, Rackspace Cloud, and GoGrid)

- ESX/vCenter (licensed) leads enterprise virtualized infrastructure

Of course, there are many more hypervisors and many different ways to deploy the three I’m referencing.

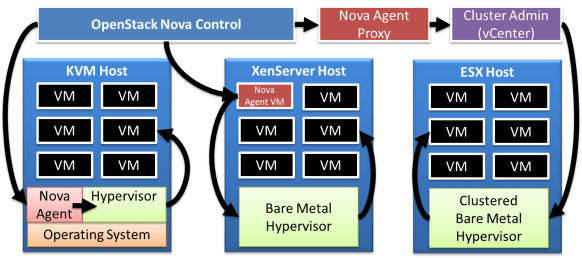

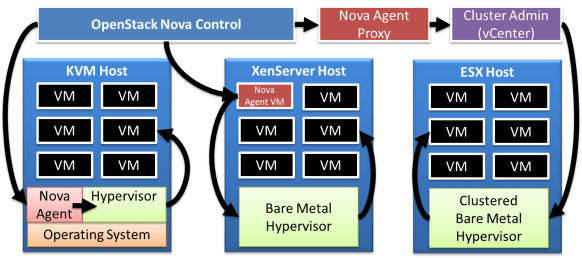

This picture shows all three options as a single system. In practice, only operators wishing to avoid exposure to RESTful recreational activities would implement multiple virtualization architectures in a single system. Let’s explore the three options:

OS + Hypervisor (KVM) architecture deploys the hypervisor a free standing application on top of an operating system (OS). In this model, the service provider manages the OS and the hypervisor independently. This means that the OS needs to be maintained, but is also allows the OS to be enhanced to better manage the cloud or add other functions (share storage). Because they are least restricted, free standing hypervisors lead the virtualization innovation wave.

Bare Metal Hypervisor (XenServer) architecture integrates the hypervisor and the OS as a single unit. In this model, the service provider manages the hypervisor as a single unit. This makes it easier to support and maintain the hypervisor because the platform can be tightly controlled; however, it limits the operator’s ability to extend or multi-purpose the server. In this model, operators may add agents directly to the individual hypervisor but would not make changes to the underlying OS or resource allocation.

Clustered Hypervisor (ESX + vCenter) architecture integrates multiple servers into a single hypervisor pool. In this model, the service provider does not manage the individual hypervisor; instead, they operate the environment through the cluster supervisor. This makes it easier to perform resource balancing and fault tolerance within the domain of the cluster; however, the operator must rely on the supervisor because directly managing the system creates a multi-master problem. Lack of direct management improves supportability at the cost of flexibility. Scale is also a challenge for clustered hypervisors because their span of control is limited to practical resource boundaries: this means that large clouds add complexity as they deal with multiple clusters.

Clearly, choosing a virtualization architecture is difficult with significant trade-offs that must be considered. It would be easy to get lost in the technical weeds except that the ultimate choice seems to be more stylistic.

Ultimately, the choice of virtualization approach comes down to your capability to manage and support cloud operations. The Hypervisor+OS approach maximum flexibility and minimum cost but requires an investment to build a level competence. Generally, this choice pervades an overall approach to embrace open cloud operations. Selecting more controlled models for virtualization reduces risk for operations and allows operators to leverage (at a price, of course) their vendor’s core competencies and mature software delivery timelines.

Ultimately, the choice of virtualization approach comes down to your capability to manage and support cloud operations. The Hypervisor+OS approach maximum flexibility and minimum cost but requires an investment to build a level competence. Generally, this choice pervades an overall approach to embrace open cloud operations. Selecting more controlled models for virtualization reduces risk for operations and allows operators to leverage (at a price, of course) their vendor’s core competencies and mature software delivery timelines.

While all of these choices are seeing strong adoption in the general market, I have been looking at the OpenStack community in particular. In that community, the primary architectural choice is an agent per host instead of clusters. KVM is favored for development and is the hypervisor of NASA’s Nova implementation. XenServer has strong support from both Citrix and Rackspace.

Choice is good: know thyself.

However, I wanted to take a minute to update the community about Swift and Nova recipes that we are intenionally leaking out to the community in advance of the larger Crowbar code drop.

However, I wanted to take a minute to update the community about Swift and Nova recipes that we are intenionally leaking out to the community in advance of the larger Crowbar code drop.